Aviation is under growing pressure to reduce its climate impact, yet progress toward decarbonisation remains slow. Business aviation, though small in scale, offers an ideal use case for new propulsion technologies because of its shorter flight profiles.

This article explores how hydrogen electric propulsion can enable true zero emission flight and why business aircraft are well suited to lead this transition. It also looks at how regional airports, supported by renewable energy and hydrogen infrastructure, can become the first operational network for clean aviation through initiatives such as ALBATROSS.

From Global Warming to the Decarbonisation of Business Aviation

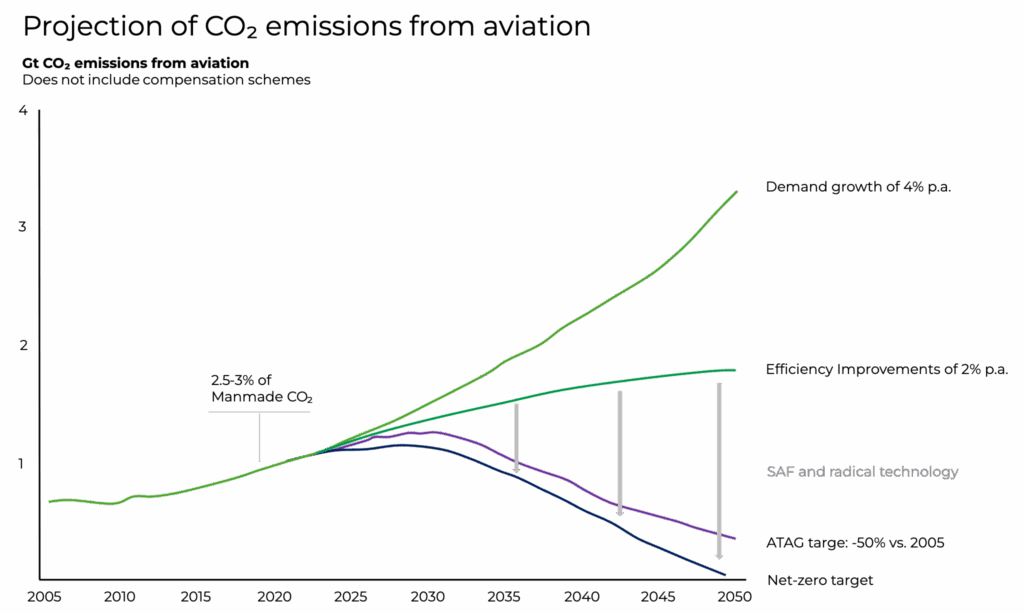

Global warming is an established scientific reality that demands rapid and sustained emission reductions across all sectors. To keep global temperature rise well below two degrees Celsius, as agreed in the Paris Agreement [1], every industry must undergo deep decarbonisation. Aviation stands out as one of the most challenging sectors to decarbonise because efficiency improvements are consistently outpaced by traffic growth and because aircraft performance is fundamentally constrained by physics. High energy demand, strict weight limits and already highly optimised aerodynamics leave only limited room for further efficiency gains.While average efficiency gains reach about one percent per year, global air traffic expands by roughly four percent. This imbalance means that even under optimistic assumptions, aviation’s share of global CO₂ emissions could rise to nearly one quarter by 2050 [2].

Figure 1: Projection of CO₂.emissions from aviation – based on [7]

The total climate impact of aviation extends beyond CO₂. Nitrogen oxides, water vapor, and contrails add significant warming effects, bringing the sector’s overall contribution to roughly four percent of total global radiative forcing [4]. Meeting Europe’s goal of climate neutrality, defined in the European Green Deal as achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions across all sectors by 2050, will require propulsion systems capable of addressing both CO₂ and non CO₂ effects [3].

Aviation’s CO₂ emissions are distributed across three roughly equal segments. Approximately one third of passenger CO₂ emissions occur on short-haul flights of less than 1,500 kilometers, another third on medium-haul flights between 1,500 and 4,000 kilometers, and the final third on long-haul flights greater than 4,000 kilometers. Very short flights below 500 kilometers contribute about five percent of global aviation CO₂ emissions [5].

Within this overall picture, business aviation occupies a distinct position. It accounts for roughly two percent of total aviation emissions, about 0.4 Mt CO₂, yet its carbon intensity per passenger is up to ten times higher than that of scheduled commercial flights, ranging from 600 to 4,000 grams of CO₂ per passenger kilometer compared with 60 to 130 grams for regional or commercial services [6]. Reducing this disproportionate footprint has therefore become a clear priority for the sector.

From a numerical perspective, business aviation may seem minor. Yet its visibility, economic importance, and concentration of short haul missions make it a natural focal point within the broader decarbonisation effort. Because the segment combines high operational intensity with limited fleet scale, it provides a realistic context for testing and validating new propulsion technologies. Its transition will be essential in demonstrating how low emission flight can perform in practice across technical, operational, and economic dimensions, setting a precedent for the wider aviation industry.

Low-Emission Propulsion and Its Application in Business Aviation

Aviation’s path to net zero requires technologies that can eliminate emissions at their source. Traditional levers such as aerodynamic refinement, lighter structures, modern engines, and optimized routing will remain part of the sector’s efficiency toolbox, but they can no longer counterbalance the steady increase in global air traffic. With efficiency gains plateauing, the industry is shifting its focus toward clean energy carriers and propulsion systems that can fundamentally replace fossil fuel combustion and deliver the deep emission reductions required for long-term climate goals [7].

Multiple technological pathways are under development, each with its own balance of maturity, scalability, and environmental performance. Current research and development programs center on four main options:

- Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF)

- Battery-Electric Systems

- Hybrid-Electric Propulsion

- Hydrogen-Based Powertrains

These differ not only in emission potential but also in operational suitability across flight ranges and aircraft classes.

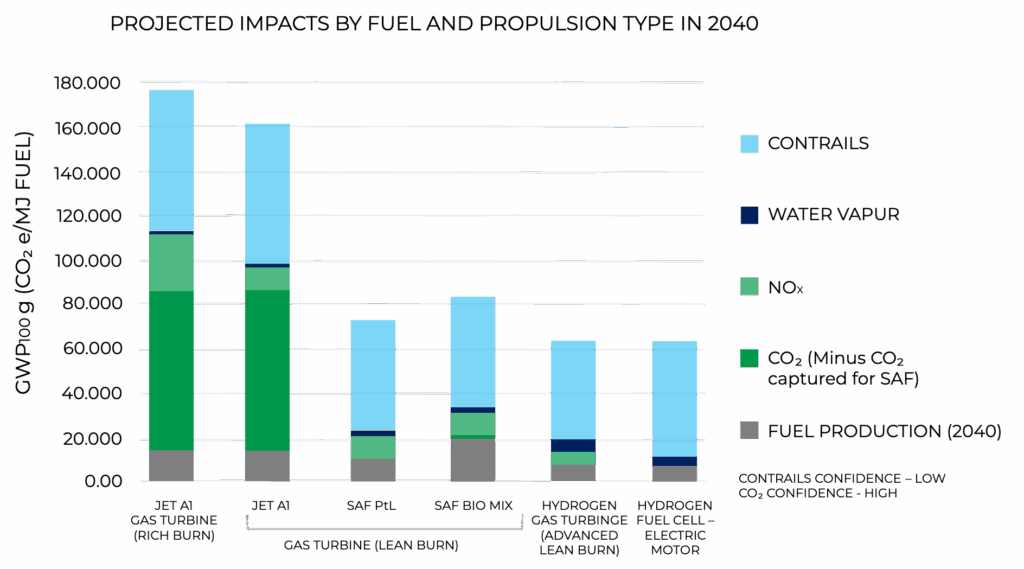

SAF can lower life-cycle CO₂ in existing aircraft but still produce NOx and contrails because they rely on combustion [6]. Production volumes remain below one percent of global jet fuel demand, and costs are several times higher than fossil kerosene [8][9], thus limiting scalability.

Battery-electric aircraft eliminate in-flight CO₂ and NOx and are very quiet, but today’s batteries have far lower energy density than jet fuel [6]. This confines the technology to small aircraft and short regional routes.

Figure 2: Projected Impacts by Fuel and Propulsion Type in 2040 – based on[3]

Hybrid systems combine batteries with kerosene or SAF, reducing fuel burn but still emitting CO₂, NOx and particulates. They also require both charging and refueling infrastructure, creating operational complexity [13].

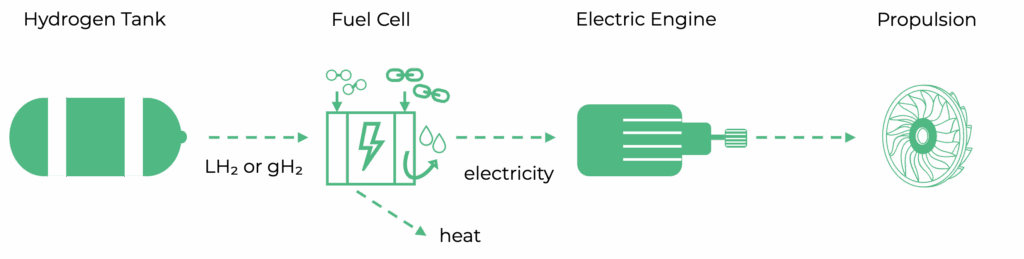

Hydrogen can be used in turbines or in fuel cells. Both eliminate CO₂ emissions, but fuel cells offer the highest efficiency and the lowest non-CO₂ climate impacts [3].

Hydrogen fuel cell electric propulsion converts hydrogen into electricity through an electrochemical process that produces only water vapor and almost no nitrogen oxides. Because there is no combustion, it emits no soot particles, which further reduces the likelihood of persistent contrails [3]. This combination removes in-flight CO₂ entirely and nearly eliminates NOx and other non-CO₂ climate effects. At the same time, green hydrogen supports a favorable long-term energy cost trajectory, since producing synthetic kerosene requires about forty percent more renewable electricity per delivered unit of flight energy [3]. Within the broader aviation landscape, business aviation presents a particularly strong use case for hydrogen fuel cell propulsion.

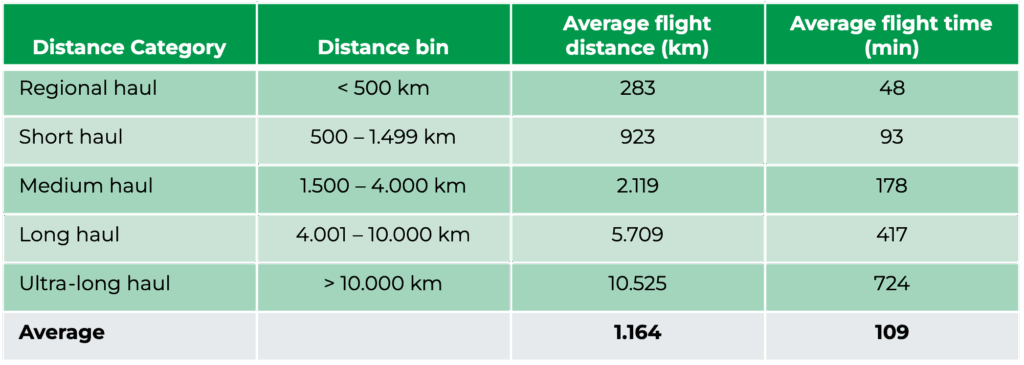

Table 1: Average flight distance and time – based on [11]

Current industry data indicate that business aviation missions are predominantly short- to medium-range. Roughly seventy percent of flights cover less than 1,000 kilometers and around ninety percent stay below 2,000 kilometers, demonstrating that hydrogen-electric aircraft can serve the vast majority of real-world operations [6].

Hydrogen’s adaptability to existing fuel logistics and its potential for on-site production make it especially practical for aviation. With modular systems for compressed or liquid storage and standardized refueling procedures already under development, hydrogen can integrate smoothly into airport operations, enabling scalable and efficient adoption across the network [6].

Across all evaluation criteria (mission suitability, climate impact, operating cost, and infrastructure compatibility) hydrogen fuel cell electric propulsion provides the most balanced solution for the decarbonization of business aviation. It fits the dominant mission profiles without compromising cabin comfort, delivers near-zero in-flight emissions, and integrates seamlessly into existing operational structures while supporting a clear transition toward scalable hydrogen infrastructure.

Beyond Aero: A Clean-Sheet Approach to Zero-Emission Business Aviation

Beyond Aero approaches the decarbonization of aviation from first principles. Rather than adapting existing aircraft, the company designs its systems entirely around hydrogen-electric propulsion. Retrofitting legacy airframes introduces structural compromises, additional drag, and payload losses while complicating cooling and balance. A clean-sheet design allows for the optimal integration of tanks, thermal management, and air distribution directly into the fuselage, maximizing aerodynamic and energy efficiency without reducing cabin comfort.

The first Beyond Aero aircraft targets the mission envelope most common in business aviation. With capacity for six to eight passengers and a range of 500 to 1,500 kilometers, it aligns directly with real-world usage. This positioning ensures both technical feasibility and immediate market relevance.

The aircraft is built around low-temperature PEM fuel cells with a target power density of about 0.8 kilowatt per kilogram, including the balance of plant (the auxiliary systems such as air and hydrogen supply, cooling, power electronics, and control units that support the operation of the fuel cell stack).

Figure 3: Simplified schematic of hydrogen fuel cell operating system – based on [13]

Its modular powertrain is scalable from sub-megawatt systems in early prototypes to multi-megawatt architectures for future regional aircraft. Development follows an iterative process of bench testing, full-scale integration, and flight validation, supported by computational fluid dynamics to optimize thermal and energy management. In 2023, Beyond Aero completed France’s first crewed hydrogen-electric flight using an 85-kilowatt system, marking a decisive milestone toward CS 23 certification.

Hydrogen introduces new safety requirements related to leak detection, flame visibility, and cryogenic storage. Beyond Aero integrates sensors, automated shutdown logic, and active ventilation into the airframe, meeting standards such as SAE AIR 8466 for hydrogen handling and refueling. Certification follows EASA’s CS 23 performance-based framework for aircraft under 5,700 kilograms, combining early regulatory engagement with progressive validation from component to system level. This structure enables rapid, evidence-based approval and positions Beyond Aero among the first to certify a hydrogen-electric aircraft in its class.

Infrastructure integration is designed for scalability and immediate deployability. Initial operations can rely on compressed hydrogen delivered through mobile trailers and dispensers, requiring minimal upfront investment. As utilization increases, airports can expand to stationary or liquid hydrogen storage, reducing logistics costs while maintaining operational efficiency. Refueling procedures adhere to existing coordination models and integrate seamlessly into Airport Collaborative Decision Making frameworks, ensuring that hydrogen operations follow the same sequence and timing as today’s workflows.

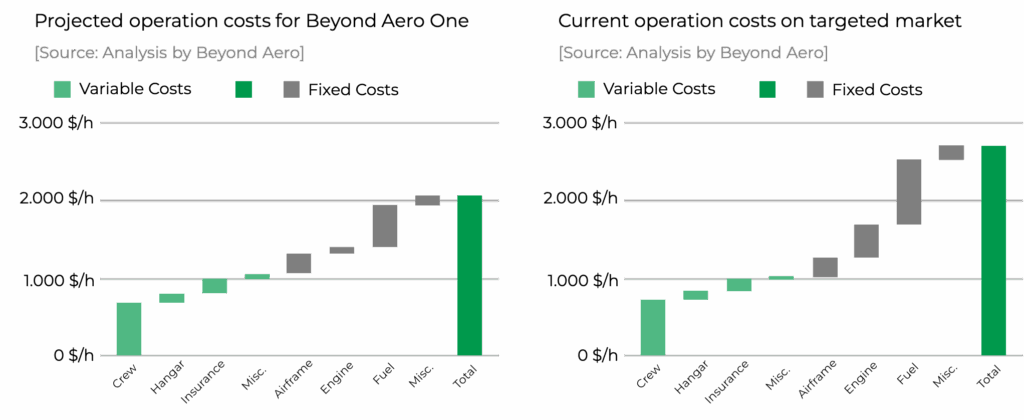

Operationally, Beyond Aero combines electric propulsion with a digital fleet management platform that connects aircraft, ground systems, and maintenance data in real time. This enables predictive maintenance, energy optimization, and integrated scheduling, approaches proven in commercial aviation but now adapted to smaller fleets. Electric drivetrains contain far fewer moving parts than combustion engines, reducing maintenance requirements and increasing aircraft availability. As renewable hydrogen production expands and energy supply chains mature, operating costs are expected to fall further. Combined with simplified maintenance, hydrogen-electric aircraft are projected to achieve at least twenty percent lower lifetime operating expenses than comparable turboprops. A study prepared by McKinsey & Company forecasts that hydrogen prices could drop lower than 3.5 $ per kg [7], dropping operating costs below Jet-A1 equivalence [6].

Figure 4: Operation costs comparision Beyond Aero One / Current – based on [6]

Market adoption of cleaner propulsion technologies is accelerating as business aviation faces growing social and political scrutiny for its high per passenger emissions. Short and medium routes, which account for roughly eighty percent of all business aviation flights, offer the greatest opportunity for measurable and demonstrable emission reductions. Demonstration programs that track real flight performance in terms of energy use, emission savings, and turnaround efficiency help regulators assess safety and reliability while giving operators and customers confidence in the technology’s practical viability.

Beyond Aero’s aircraft generates valuable operational data that informs policy development and supports the broader transition to hydrogen electric flight. Research into non CO₂ climate impacts complements these efforts, with flight tests monitoring exhaust composition, humidity, and contrail behavior in cooperation with meteorological experts. The insights gained support the creation of operational procedures that minimize contrail formation through adaptive routing.

Hydrogen electric propulsion is now entering practical implementation. With design, certification, and infrastructure development advancing in parallel, the foundations for zero emission business aviation are already being established. Clean sheet aircraft, modular hydrogen powertrains, and digitally managed operations provide a scalable path toward net zero aviation.

Regional Airports as the Foundation of a Hydrogen Aviation Network

The next stage in the transition toward zero emission flight will be the implementation of hydrogen infrastructure. Studies identify regional airports as the most suitable environments to begin this transformation [12]. Their smaller scale, simpler operations, and lower air traffic complexity allow for faster adaptation of new energy and refueling systems without the logistical challenges found at major hubs.

Regional airports account for a significant share of total flight movements in Europe, often serving short to medium distance routes that align perfectly with the range capabilities of hydrogen electric aircraft. Hydrogen demand can initially be met through compressed hydrogen delivered by mobile trailers or on site electrolysis. This decentralized approach allows scalable deployment without heavy upfront investment, while maintaining operational continuity with existing fueling logistics.

When combined with local renewable energy generation, such as photovoltaic systems and battery energy storage, the concept gains even more traction.

ALBATROSS envisions regional airports as self-sufficient energy nodes that produce, store, and distribute green hydrogen directly where it is needed. Electricity from solar panels is converted into hydrogen through electrolysis and stored either in compressed or liquid form. This stored hydrogen can then power both ground operations and aircraft refueling, creating a closed loop of local, zero carbon energy use.

Such integrated systems not only reduce aviation emissions but also strengthen regional energy independence and economic resilience. Each airport effectively becomes both an energy producer and a transport enabler. Over time, connecting these airports through coordinated operations and standardized hydrogen handling protocols would create a continental network of clean aviation corridors.

Regional airports therefore represent not only a feasible entry point but also a strategic platform for scaling hydrogen-powered flight in real operational conditions.

Sources:

[1] Paris Agreement – https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement

[2] Roland Berger – Hydrogen: A future Fuel for Aviation? – https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Insights/Publications/Hydrogen-A-future-fuel-for-aviation.html

[3] FlyZero – Sustainability Report- https://www.ati.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FZO-STY-REP-0005-FlyZero-Sustainability-Report.pdf

[4] Quantifying aviation’s contribution to global Warming – https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ac286e/pdf

[5] ICCT: CO2 Emissions From Commercial Aviation – https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ICCT_CO2-commrcl-aviation-2018_facts_final.pdf

[6] Beyond Aero Whitepaper – https://prowly-prod.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/uploads/landing_page_image/image/612489/15601a7c31381424b7815d36c45e1df3.pdf

[7] Hydrogen-powered aviation – A fact-based study of hydrogen technology, economics, and climate impact by 2050, Publications Office, 2020 – https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2843/471510

[8] IATA: Disappointingly Slow Growth in SAF Production – https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/2024-releases/2024-12-10-03/

[9] Aireg: Economy and Production: https://aireg.de/economy-and-production/#:~:text=High SAF Production Costs,fossil kerosene (see figure).

[10] sopp+sopp – Hydrogen Fuel Cells vs Hydrogen Combustion Engines – https://www.soppandsopp.co.uk/news/hydrogen-fuel-cells-vs-hydrogen-combustion-engines#:~:text=While hydrogen engines are carbon,hydrogen fuel cells (HFCs).

[11] ICCT: Air and greenhouse gas pollution from private jets, 2023 – https://theicct.org/publication/air-and-ghg-pollution-from-private-jets-2023-jun25/

[12] LH2 supply for the initial development phase of H2-powered aviation (Schenke et al., 2024) – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386058370_LH2_supply_for_the_initial_development_phase_of_H2-powered_aviation

[13] IATA: Concept of Operations of Battery and Hydrogen-Powered Aircraft at Aerodromes – https://www.iata.org/globalassets/iata/publications/sustainability/concept-of-operations-of-battery-and-hydrogen-powered-aircraft-at-aerodromes.pdf